Researchers Use SyracuseCoE CARTI Grant to Study the Management of Salt Application on Fishkill Creek

Read the publication: Salting our landscape: An integrated catchment model using readily accessible data to assess emerging road salt contamination to streams

- See the SUNY Cortland faculty page for Dr. Li Jin

- See the University of Oxford faculty page for Dr. Paul Whitehead

- See the Syracuse University faculty page for Dr. Donald I. Seigel

- See the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies research page Dr. Stuart Findlay

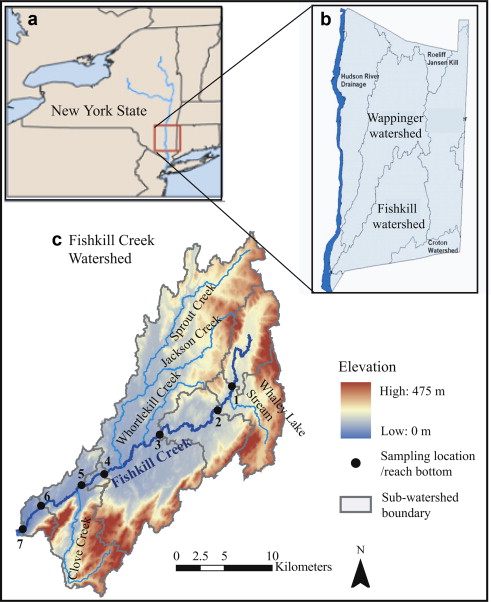

While not particularly thought of as a health hazard, high levels of salt are being found in streams and groundwater—affecting our watershed and therefore our overall water quality. Through SyracuseCoE-funded research conducted in Fishkill Creek in Dutchess County, NY, Stuart Findlay of the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, along with Don Siegel and Li Jin of Syracuse University, found that the major culprits are road salt (contributing to more than 80% of the issue), water softeners (5-10%) and wastewater treatment plants (about 1%).

While not particularly thought of as a health hazard, high levels of salt are being found in streams and groundwater—affecting our watershed and therefore our overall water quality. Through SyracuseCoE-funded research conducted in Fishkill Creek in Dutchess County, NY, Stuart Findlay of the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, along with Don Siegel and Li Jin of Syracuse University, found that the major culprits are road salt (contributing to more than 80% of the issue), water softeners (5-10%) and wastewater treatment plants (about 1%).

While it’s easy to assume that streams and groundwater are more contaminated with salt in the winter months when there is a large amount of road salt application, the opposite can be equally true. High concentrations of salt have been found in the summer months—painting a clear picture that something is holding onto the chloride, making it last through the summer and perhaps affecting animals in the streams during their breeding season and their young in early growth stages. In Dutchess County, NY, about 20% of the private wells show salt contamination at levels that would advise caution for people on severely salt-limited diets. Since large areas of New York rely on individual water wells, it presents a problem once the groundwater is contaminated. It may take a long time to see rising salt levels in groundwater and it will also take a long time for levels to decline, even if salt applications are reduced.

Through a new model, researchers found that by reducing salt application in half, the concentration decreased by only 20.7%, while doubling it increased concentration by 34.2%. The model suggests a lag in delivery of the salt, so the road salt applied now will more than likely show up in the future. These results provide an educational model that help us manage expectations of what is down the line for our watershed if we don’t act to mitigate salt levels in the water. Next, there is a need to find modifications to road salt, different ways to apply salt so it remains only on the road and/or begin to reduce the application rate.

“Salt pollution of our environment is an increasingly important issue,” Findlay tells us “but the bright side to the problem is that it can engage citizens and local officials to be more aware of apparently benign materials we spread into the environment that can come back to trouble us.”

- See published research for Dr. Li Jin

- See published research for Dr. Paul Whitehead

- See published research for Dr. Donald I. Seigel

- See published research for Dr. Stuart Findlay